Mediapart

A group of driven and accomplished French journalists in search of a new business model for creating a profitable independent press online.

What is it?

After former editor-in-chief Edwy Plenel left French daily Le Monde in 2005 as a result of a fundamental dispute about the ownership of the newspaper, he joined his former managing editor Laurent Mauduit, former Libération editor-in-chief Gérard Desportes and François Bonnet (Le Monde, Libération, Marianne) to launch a new journalistic project.

Only our readers can buy us

Mediapart sought to be independent from advertising revenues and companies that are not primarily concerned with journalism, like the ones that own Canal+, Le Monde, Libération, and many other media outlets in France. A poster in Plenel's office reading "Seul nos lecteurs peuvent nous acheter" (“only our readers can buy us”) reminds the journalists of this objective every day.

The founders insist Mediapart is not a website, but rather an online newspaper focused on investigative journalism while also covering current events. "From the start, for us, it has been newspaper. It is not a site, it is a newspaper. Yes, it is a newspaper. And I think we are really showing what a digital newspaper can be," emphasizes Plenel.

They always aim to cover the current events from a different angle, using sources that do not usually appear in the traditional media. This is what according to editor-in-chief François Bonnet makes for the original editorial line of Mediapart.

Launching a newspaper online obviously costs much less than creating a print newspaper, but the founders also believe the online format has particular advantages. Publishing online provides journalists unlimited space, allowing the story to dictate the length and format of the piece, and provides opportunities to embed hyperlinks and interact with their readers.

How does it work?

Mediapart was meant to address what its founders perceived as a three-fold crisis in journalism with economic, moral and democratic dimensions.

To address the economic crisis, they needed to invent a business model for journalism that did not rely on debt, investment and advertisement revenues. Against the prevailing wisdom in 2007, which claimed that charging for online content would not work, they decided on a subscription model. Apart from the headlines and the first paragraph of each article on the home page, the longreads, podcasts and web documentaries are behind a paywall.

The homepage is updated three times a day, producing three daily editions with articles organised according to relevance instead of time of publication. Sometimes an article with very high relevance is even published in multiple editions. This distinguishes the online newspaper from news sites, where the most recent article is also on top of the homepage.

Subscribers can furthermore contribute blogs and discuss with journalists in the Le Club section of the website, which is also accessible to non-paying readers. A subscription costs 11 euros a month.

Why does it succeed?

The founders were journalists on a mission; apparently, it was one that resonated with a sufficient number of people. As the president of another French start-up put it: “I don't think Mediapart's subscribers all read the newspaper on a daily basis, but they feel like being a part of it.” Mediapart has come to resemble a community. Many of its subscribers see it as supporting a cause.

To communicate this mission they had a very charismatic spokesperson in president Edwy Plenel, who employs a clear discourse and has a strong journalistic reputation. While editor-in-chief François Bonnet manages the editorial line and content production, Plenel makes sure the Mediapart story is heard in the outside world.

In order to fulfill their promise to publish quality content, Mediapart started out with a substantial team of 25 qualified journalists. They account for 2,5 million euros annually in employment costs; 70% of the total capital needed to create and run the online newspaper. Luckily, the founders were reputable and accomplished journalists, who invested a total of 1.325.000 euros of private capital. Also, they had a network of friends and acquaintances that together contributed 504.000 euros.

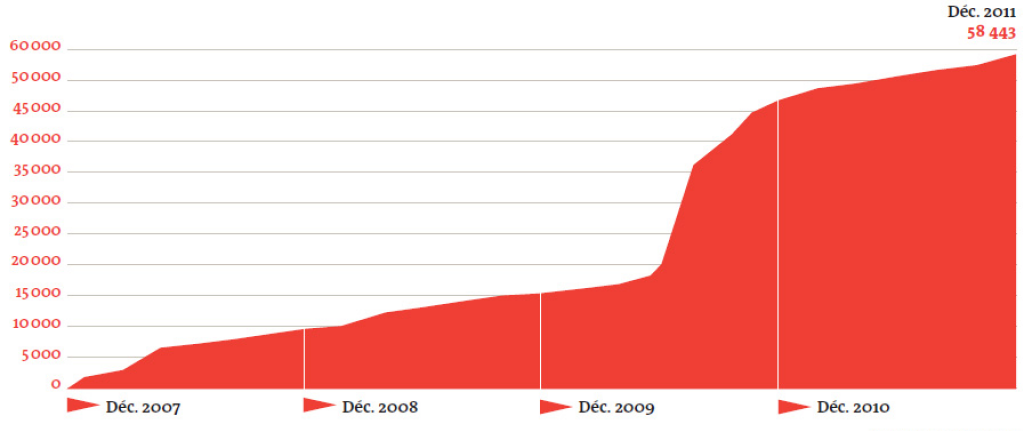

To develop their audience, they cleverly made use of opportunities when they came along, with the Bettencourt affair being the most important one. Publishing secretly taped phone calls that other media had passed on allowed for a major scoop, leading to extra media attention and a consequential doubling of the number of subscribers in the 6 months that followed.

Why did we select it?

Mediapart shows that there are business models available for making independent online journalism profitable. While researchers (Witsche & Nygren 2009) note increasing pressure on online media to sell out in order to attract more readers—and thus advertisers—in order to survive, Mediapart aims to be completely funded through paid subscriptions in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Mediapart’s readers are willing to subscribe to the online newspaper for 11 euros a month. Although a large part of their capital is still accounted for by the investment of the founders’ private money, they have been profitable since autumn 2010 and are working towards creating a foundation to use these profits to buy out the initial investors and become completely funded by its readers. For Mediapart’s founders, financial independence is a means to editorial independence.

When the online newspaper was launched in 2007 many believed it would fail, because its paid subscription model was still untested. This makes them a pioneer in new business models for online journalism. Ad revenues have been falling for years, forcing journalism to find revenue sources (Naldi and Picard 2012, Bruno and Kleis Nielsen 2012). However, few alternative options are available. And many of those who have tried charging for online journalism have failed.

Readers are willing to support what they consider good journalism

Though Mediapart seems a rare case, its success reminds us that there is no excuse to not do journalism the way you think it should be done. Mediapart shows first that it is possible to find a new viable business model for online content, and second, that readers are willing to support what they consider good journalism. Just like the readers of De Correspondent in The Netherlands, for example.

Extra

The English translation of the audio interview above with co-founder of Rue89 and Brief.me, Laurent Mauriac:

“For my part, I think Mediapart’s success is two-fold. It’s a journalistic success, but not merely that. I think that it has also been a success in the motivation of Mediapart’s readers, and that’s linked to the personality of Edwy Plenel and the strength of his convictions. I think there’s also the idea of membership, of supporting a cause—a bit like a club in fact."

"And I think that the readers, the people of Mediapart, are proud to subscribe. But they don’t have a relationship with Mediapart like with traditional media, which is to say I am not sure that all subscribers of Mediapart read it everyday, for instance."

But they are members everyday?

"They are happy they are members, there’s a feeling of membership, exactly."

And you have learned something from Mediapart as well, or it’s a specific case?

"I think that it’s a specific case, yes. I think that Mediapart often says, look, we are a laboratory and we show the way for other media. But for my part I am a bit skeptical about the possibility of applying this formula. I think it’s a unique case."

Why?

"Because as I explained, the personality of Edwy Plenel and all the stories that have emerged, the feelings of membership, the notion of subscribing, these are all things that are difficult to replicate."

The English translation of the audio interview above with Mediapart's president Edwy Plenel:

“There were several challenges. First, we faced the challenge of independence. And, second, we faced a challenge of experimentation with respect to those who, in 2007 and 2008 when the project was conceived and launched, said that information was free on the internet—that information should be free on the internet. Everyone was saying that people wouldn’t go to just a newspaper but that people would surf around and that news readers were the trend. The other nonsense people insisted upon at the time was that the internet implied short formats.

Basically, those three things refer to what sociologists would consider to be “technical illusions”—this idea that it’s the technical side that shapes how things are used, whereas it’s the way things are used that determines what we do technically. Unless we let ourselves be dominated by it. But it’s the ways things are used that allows us to do things. And we have shown that with the internet, people were ready to read a newspaper, to become loyal as an audience, and that hyperlinks also allowed them to do richer, more profound, and more lasting things than could be done in the confines of a printed paper.

And we showed that all of this could create value, because every industrial revolution is a battle about value. There’s a battle over distributing value and a battle over creating value. So we wanted to show that we could create value and to do it in a way that would profit those who create rather than the shareholders."

This contribution is based on the master thesis Beyond Journalism: Charging for online journalism is not such a ridiculous idea after all - a case study of the French online newspaper Mediapart. It was conducted by Andrea Wagemans as part of the larger research project Beyond Journalism.